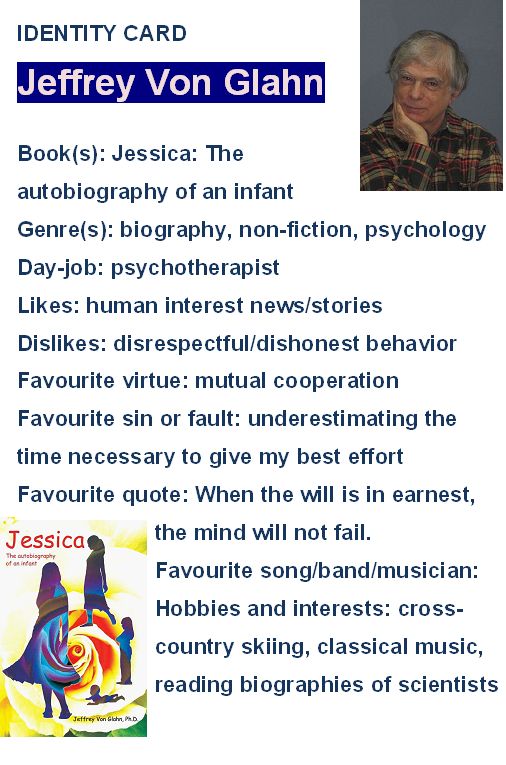

Some authors are writers, some teachers, some journalists, etc. My guest today has a unique source of inspiration – he is a psychologist, by profession and vocation. To use an old cliché, Jeffrey Von Glahn is here, on the interview couch, to answer some questions. See who analyzed who(m);)!

1. Your book is Jessica: The Autobiography of an Infant, which is kind of a paradox in itself. How did the idea first come to your mind to write that true story as a book?

I made a firm decision to write the book – although I had certainly been thinking about it – when Jessica exclaimed immediately following her remembering another very early experience, “What’s happening here is too important to keep to our selves.“ I was greatly relieved. I could stop worrying about asking her what she thought of that idea and possibly having to talk her into it as she’d be the star (anonymously, of course) of the book.

The full title had to serve two functions: Get the prospective reader’s attention, and in as few words as possible capture the unique feature of the book. The use of “autobiography“ seemed a perfectly logical term for Jessica’s reporting, as if she had in fact become an infant again, every psychologically dramatic moment of the first few weeks of her life as it was happening.

Here’s an excerpt from the Foreward. It reveals why I had to write the book.

Listening to Jessica during therapy sessions was the same as listening to an infant who could talk describe in vivid detail every psychologically dramatic moment of its life as it was happening. As a result, my perception of infants was radically altered. I will never again think of them as simple little beings primarily interested in eating and sleeping. They are far more complex than I had ever imagined. When I am now in an infant’s presence, I am acutely conscious that an active force in the world is before me. What I say and how I act will be watched with great interest by a mind that, though not as developed as mine, is probably more curious about the world and definitely more s ensitive to it.

Infants, especially newborns, pull me toward them with what seems like an irresistible power. Whenever I see one of these brand-new human beings, I must fight my urge to drop whatever I’m doing and immediately rush to its side. In my fantasy, I see myself slow down as I approach my goal and unhurriedly cover the last bit of distance. I close in with the most incredibly joyous smile anyone has ever seen. My eyes bulge in unabashed delight, while my smile and eyes speak for me. They speak the language of infancy, a life rich in feelings, hopes, dreams, potential, and an insatiable curiosity about the world. It is a life as exciting and intriguing as anything adults can even imagine.

2. Your long-term day job is a therapist, and you say you’d come back as one if you believed in reincarnation. What makes the job so interesting? Is it sometimes difficult to separate your clients’ stories from your personal peace of mind?

A better terminology. Being a therapist isn’t a “job.“ I’ve done it long enough so that I don’t have to think about how to do it. I can give my full attention to the client rather than wondering if I’m following some theory about what I’m supposed to be doing. I find being a therapist – at least in my way of being one – as truly fascinating. There’s nothing more exciting or of more compelling interest than human experience, and there’s no endeavor that’s more worthwhile than helping someone to improve their life in some significant way. And in doing so, my view of my role as a therapist is that I’m just one person trying to help a fellow human being in a time of need. That’s a perfectly natural thing to do. It doesn’t feel like “work“ or a “job.“ And I get to use all of my intellectual skills as well as all of my caring instincts at the same time.

Somewhere in the book I wrote that when I’m able to help someone regain contact with a part of their basic humanness they had lost contact with because of hurtful events in early childhood, I feel like I’ve help to give birth to a brand new human being.This can only happen following deep crying, and with some people it only takes a minute or two of that depth of crying. The change in the person’s overall psychological state is so dramatic that this is the only possible way I can describe it. It’s in their face and their eyes and their posture and their voice and their behavior. They’re “alive“ in a way they’ve never, ever been.

The only time clients’ stories have interrupted my “peace of mind“ was in the first year or so of my being a therapist. Here’s an example from my internship many years ago. My twenty-six year old client contracted polio at age six. Shortly after the diagnosis, her favorite grandfather visited her in the hospital. The next day her mother told her how upset he was after seeing her, certainly a natural reaction for an adult relative to have but one a six-year old shouldn’t hear about. When he didn’t show up for a few days, my client learned from her mother that he had suffered a stroke and died, and unfortunately, and quite innocently, added the words, “after visiting you.“ The next morning my client noticed that one of the boys in her ward was gone. A nurse said he had died during the night and he’s now with God, and she too, unfortunately, added, “God only takes good children.“ When my client was taken for her daily whirlpool treatment, this time she resisted with all of her might. In her mind, the swirling water was a sinister whirlpool that was going to suck her under and she’d be punished for having caused her grandfather’s death. And the fact that she was still alive was undeniable proof that she had done so. My client cried deeply for a few minutes while revealing all of this and was completely free of the “false“ guilt she had struggled with for 20 years.

For some weeks after this experience, I couldn’t wait to tell everyone I knew. I always started with, “You won’t believe this!“ I had no idea at the time that people, and especially children, could be affected in such a way. Reading case examples in class was a poor subtitute. You have to see it with your own eyes. I didn’t know at the time that I’d end up hearing many more similar childhood examples.

3. What do you love and hate about your main character – Jessica? Why did you tell her story?

I absolutely loved Jessica’s commitment to regaining her full humaness. I dedicated the book to her and to a mentor of mine. It was her bold request for longer sessions – 3-4 hours a day for several days week – that established the conditions for all of this to happen. Her story had to be told, and since I was the only witness no one else could write it in quite the way that I could. It took me several years to realize that even though it was a true story, I had to write it in the style of fiction; i.e., appeal to the reader’s emotions, or “showing,“ rather than their intellect, or “telling.“ As someone with two graduate degrees, I was rather adept at the latter. It took enough rejections from agents for me to realize I’d better learn how to “show“ instead of “tell.“ I finally found an agent who was impressed enough to submit it to publishers. Unfortunately, this was in Dec. 2001. After she received “No thanks“ after “No thanks,“ she informed me that I was also another victim of 9/11. Publishers weren’t taking any chances on a type of book without any history in sales. So I became in indie author.

4. You claim that crying is the turning point in therapy or healing. Why do you think so?

The main reason I think so is because of the many hundreds of examples of it I’ve seen. What I think of as “therapeutic crying“ in my professional articles produces the most dramatic change. This kind of crying occurs spontaneously when the person is being listened to attentively rather than it being forcefully triggered by an unexpected event. I’m convinced that there’s a natural healing process for psychological “injuries“ just as there is one for physical injuries/illnesses. Both processes operate in the same way: Protection from further injuries/illnesses and sufficient support. In medicine, support is physiological in nature, while in psychotjerapy it’s the therapist (or someone else) listening attentively.

5. Are you working on a new book right now? Being a psychotherapist, you certainly need not look far for inspiration, but you must struggle with finding the balance between divulging too many personal details and getting the story across. How do you hold to that thin line?

I have ideas for two short books, but I haven’t started to write either one yet. One’s on straightening out psychotherapy. At present, crying is not recognized as a good thing for clients to experience. In fact, many of my colleagues believe that if a client becomes “too upset“ that he is being “re-hurt“ all over again. Every work day in many countries in the world tens of thousands of clients cry. All the mental health system (I hate that term) can advise is: Calm the client down as quickly as possible.

The other book is what a society would be like if the only function or task of government was to promote the physical and psychological welfare of its citizens. In such a society, for example, companies wouldn’t be allowed to make money off of people being sick. Medical decisions wouldn’t be based on “How much will it cost?“ Gasoline (petrol) companies would announce a week before a holiday weekend that they might have to raise prices. Society would be based on cooperation and trust and a mutual interest in each other’s well-being, rather than on competition and mistrust. We’d all wake up in the morning and immediatley wonder how we might improve our own overall well-being as well as that of those around us. I intend this book mainly for my fellow citizens in the USA. Too many of them suffer under the illusion/delusion that they are the only citizens in the world who haven’t been brainwashed – there’s no other term – into believing that we live in the most rational society that’s ever existed.

6. Do you have a trusted alpha-reader who gets to read along as you write? What was the best piece of advice you’ve gotten so far on writing?

The best piece of advice I ever received was in the form of a compliment. My initial attempts to practice writing were short stories. A very intelligent woman friend of mine read one and said, “Any question I had in a sentence was immediately addressed in the next one.“ I immediatley realized that that’s how I track a client’s experiencing. What was left unsaid I always ask about. In writing, my narrative is tied together

by what the character is experiencing rather than just a description of some of the e situation followed by the author saying/telling “She/he thought/felt/feared/etc.“, rather than describing (“showing“) the character’s reaction to feeling afraid/etc.

7. Many people say that writing is also a form of (auto)psychotherapy. Would you agree and why?

While helpful, at best it has a small positive effect on one’s psychological health. There’s no substitute for person-to-person contact.

8. Which problems in the modern-day world make you want to pick up the pen and write about them? Do you think books and words can still have a powerful effect on people?

First question: Psychological development – that which determines far more than anything else how we experience being alive, how we interact with others, and how we view the world – begins at least by birth, and very likely before that. So what’s the most important job in the world: Raising an infant. And the second most important job: Helping those who didn’t benefit from that kind of an ongoing experience to recover from any adverse effects that resulted. Since society as a whole will benefit from a person regaining contact with their basic humanness, it should be a free service.

Second question: Absolutely. Words/ideas serve as guidelines, as working theories, for how we behave.

9. Since Jessica shares her infant memories with the readers, could you share one of yours perhaps? For instance, as a little boy, what did you want to be when you grew up? Which book left the strongest mark on you when you were a child?

I think my first desire for when I grew up was to be a detective. My favorite radio program (we didn’t have a TV yet) as a yound child was Dick Tracy, and his new piece of technical equipment: A wrist-watch that also served as a two-way phone with anyone who had this wrist-watch. He was a detective and he solved mysteries! That seemed really exciting. That’s a part of what I experience as a therapist, tracking down the early experience(s) that caused my client’s current problem(s).

10. Would you like to add anything about your current work or send a message to the readers?

This is for the writers among the readers, and it’s only for those writers who weren’t born with the gene for writing, assuming there is one. If you believe you have that gene and/or that you’re just a “natural“ writer, you’ll probably find the rest of this as quite boring.

For those of us who don’t have the gene, writing is a skill that has to be developed. And as with any skill, it can only be developed through practice. The key to effective practice is having a specific focus. Ball players, for example, don’t become better hitters just by holding a bat and swinging it at an imaginary ball, just as beginning writers don’t become better writers by staring at a page and imagining how they’d re-write it. For athletes who practice and practice, their expertise is attributed to “muscle memory.“ Repetitive practice trains the muscles to respond in a particular way in the same situation. When ballplayers practice batting, they have a specific focus: e.g., shifting their weight, when to start the swing. If you don’t have a teacher or a coach who tells you what to practice, you need to make up your own practice assignments. When you were in school, tests and homework served that purpose. They forced you to concentrate. Now you have to do that for yourself. My favorite way to practice writing, and “showing“ in particular, is to use the first few paragraphs of an ebook by an indie author. Books by indie authors are primarily fiction and practically all of them have too much “telling“ rather than “showing.“ My self-assigned homework project is to re-write the opening paragraphs in that way. It does takes time and concentration. Quite often, I don’t have a confident enough of a feeling at the start whether I can create an improvement or not. When I don’t have a clear sense of how to start, I’ve discovered that if I jot down a best guess for how to start the first sentence, even if just a few words, there’s an immediate response in my head. It’s like my brain is saying, “No. Do it this way.“ It seems to me that the brain responds quicker when it has something it can see. When I think I’m done, I send it to my best friend, a university English professor for his feedback.

The point of all this is that your brain is your best ally in writing, even though it doesn’t always feel that way. Your brain does want to cooperate with your desire to learn something new or to improve your skill at writing. It can’t wait for you to give it more of your experience so it can process that information and add it to your accumulated fund of what you’ve learned; i.e., the intellectual version of “muscle memory.“ Practice makes the neural connections respond together, just like the muscles. The more you re-read, even if only for 10-15 minutes, and re-write, which of course, requires more time, the better you’ll get.

Website

Twitter: @JeffreyVonGlahn

Excellent interview. This was a wonderful and enlightening book.

LikeLike

Fascinating interview, you two! Anita, have you ever had any career experience in journalism? If not, you should consider it! You are an amazing interviewer with questions that are quite out-of-the-box 🙂 I enjoyed this very much!

LikeLike

Thanks, Traci! I think Jeffrey deserves the credit! Amazing man!

LikeLike

I agree with Traci. Your questions showed initiative on your part and a desire to find what was unique about me and the book and encouragement for me to expound on anything I thought might be on interest to others. I’ve felt straight-jacketed by other interviewers with their formulaic questions.

LikeLiked by 1 person